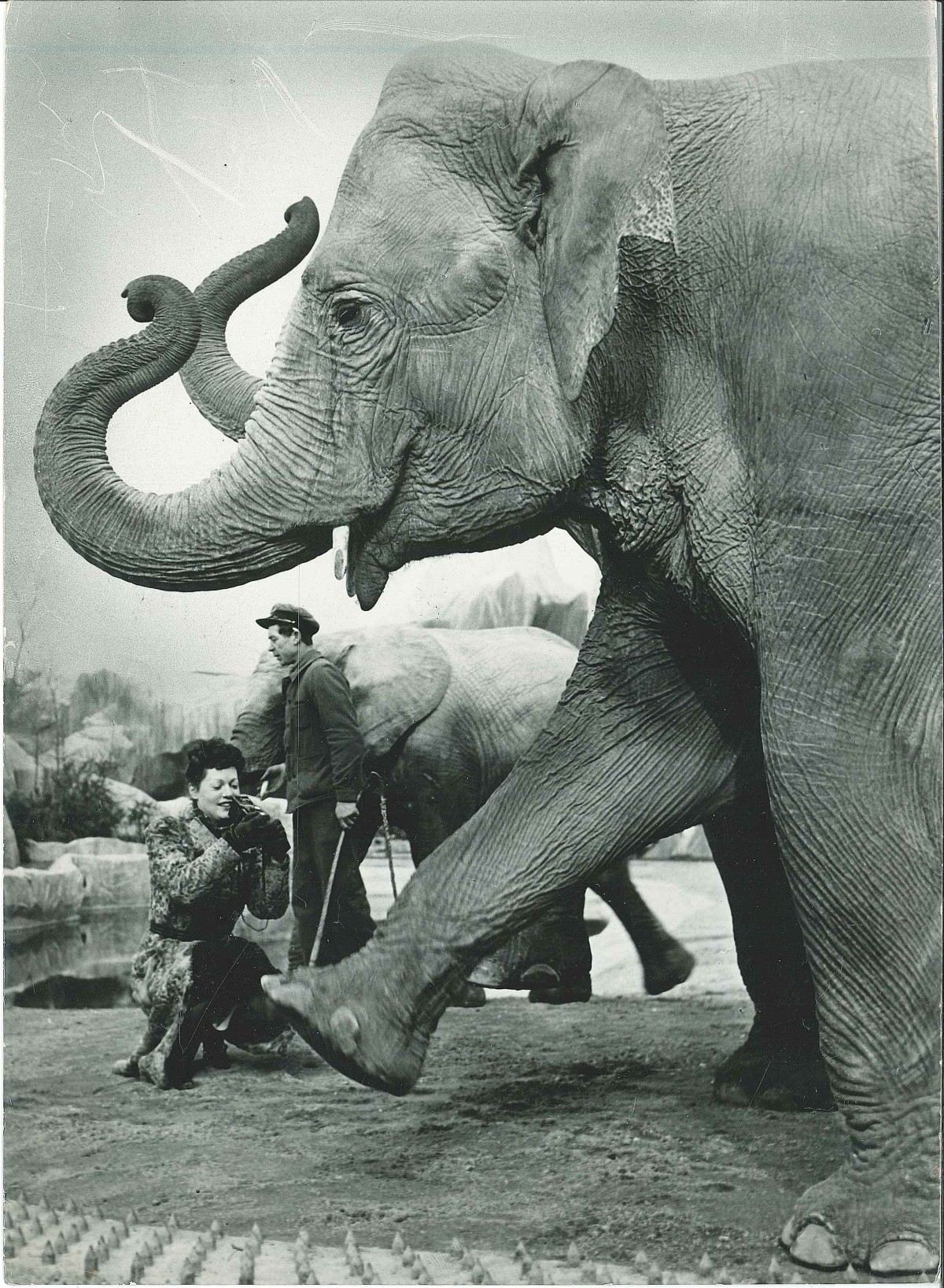

The animal photographer Ylla (1911–1955) was a celebrity in her time. She was said to be the best specialist in her field. What made her so exceptional: Ylla, actually Camilla Henriette Koffler, knew how to engage with animals as models and portray them as individuals with their own animalistic character traits. The photo taken of her in the late 1930s by her mentor and friend Ergy Landau shows her at work in a Parisian zoo. With astonishing fearlessness, Ylla crouched down in front of an elephant as if nothing could happen to her. She held the camera so that she could capture the colossus’s head from below. As a photographer living her dream and as a model for a photo that documents her dangerous work, she smiles into the viewfinder. She knows what a unique person she is: a woman who dares to get as close to wild animals as the majority of her male competitors would never have ventured.

07. March 2025

Expo Window

Expo Window: The Girl with the Elephants

by Andrea Winklbauer

Ergy Landau

The animal photographer Ylla at work, ca. 1939

Silver gelatin paper

Jewish Museum Vienna

In the first half of the twentieth century, it was not easy for women to take up a creative profession. Male-dominated colleges, associations, and organizations tried to exclude female competition for as long as possible. However, photography was much less highly regarded than painting, sculpture, or architecture. The training opportunities were also more accessible and the men’s networks even less established due to the relative newness. These two factors made it easier for women to gain entry into this profession. In Vienna, for example, the Higher Federal Institution for Graphic Education and Research offered women a full training as photographers “as early as” 1908, while the Academy of Fine Arts did not admit aspiring female sculptors and painters until 1920.

Among the many young women who wanted to become photographers in Central Europe in the interwar period, there were a particularly large number of Jewish women, many of them from bourgeois families, some from the upper class as well. This peculiarity is explained by the fact that acculturated Jewish families were more willing to allow their daughters to receive an education and a professional career than families from the Christian majority societies, which for a long time held on to a patriarchal image of women. As a result of this attitude and the ambition of the daughters the innovative and still famous female photographers of the interwar period were mainly Jewish women.

One of them was Ylla. She was born in Vienna on August 16, 1911, to Margit Leipnik, a Hungarian from Sisak (Croatia), and Max Heinrich Koffler, a businessman from a wealthy, noble family in Brăila (Romania). In her youth, Ylla introduced herself as Hungarian, but later she is said to have emphasized her Romanian origins. The American film director Howard Hawks thought she was German. Camilla Koffler spent the first years of her life in Vienna, but also on journeys taken by her businessman father. After the end of the First World War and the separation of her parents, she lived in Budapest and then in Belgrade, where she began studying sculpture at the Academy of Fine Arts in 1926. During this time, she changed her first name to Ylla. At the end of 1931, she moved to Paris to continue her sculpture studies at the Académie Colarossi in Montparnasse. In need of money, she took a job as an assistant in the photo studio of the Hungarian-Jewish photographer Ergy Landau.

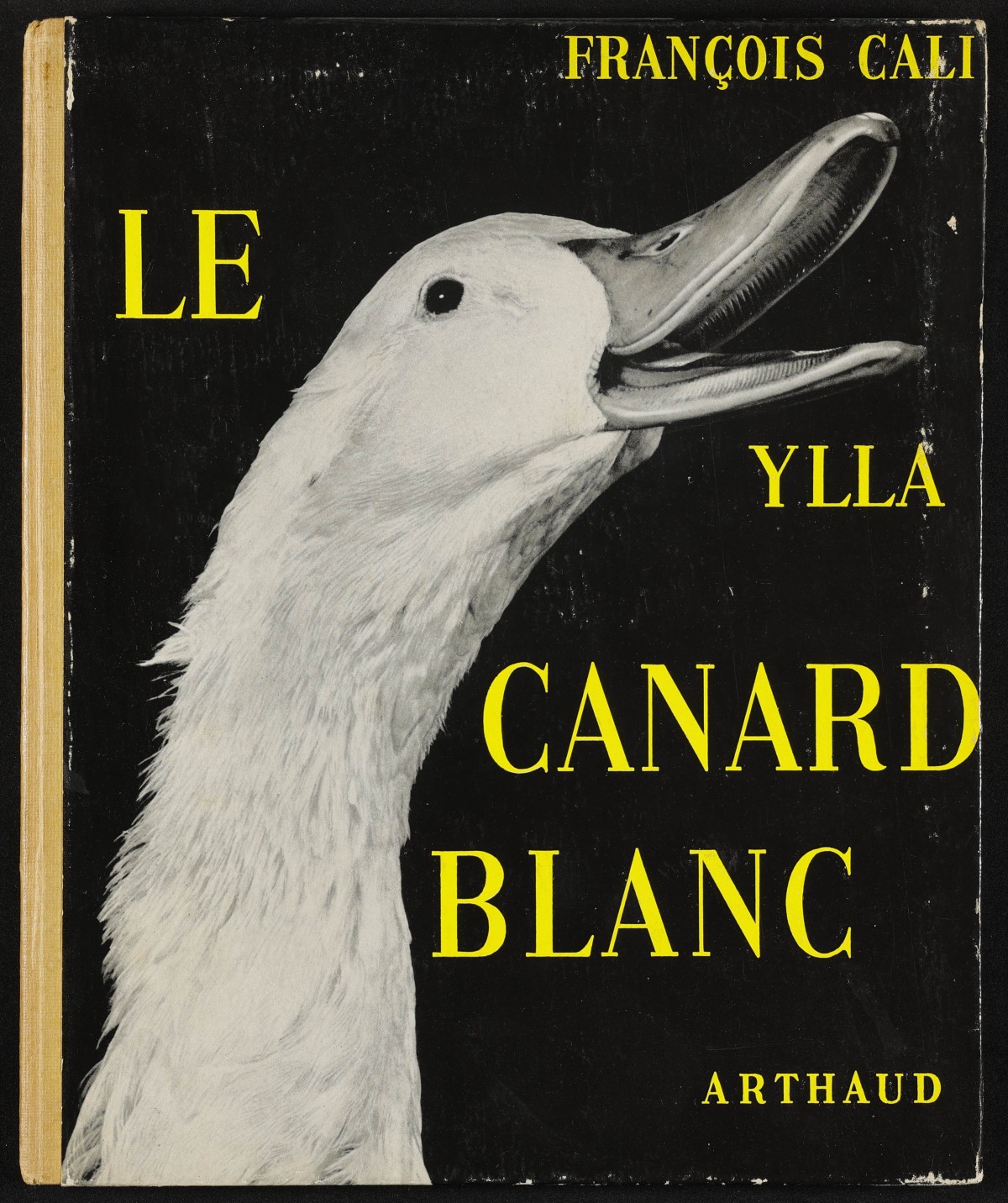

Ylla, Le canard blanc (The Duck), 1937

The meeting with Landau proved to be a stroke of luck for the twenty-year-old, because she not only discovered her own talent for photography but also received encouragement from her boss and later friend. This support was all the more helpful as Landau was well-connected in the Parisian avant-garde scene. Erzsébet Landau (1896–1967) had completed an apprenticeship with the Hungarian photographer Olga Máté in Budapest in 1918 and then studied with the portrait photographers Franz Xaver Setzer in Vienna and Rudolf Dührkoop in Berlin. After returning to Budapest in 1919, Landau opened a studio and exhibited her own work for the first time. In 1923, she moved to Paris. Changing her first name to Ergy, she opened the “Studio Landau” at 17 rue Lauriston in 1924.

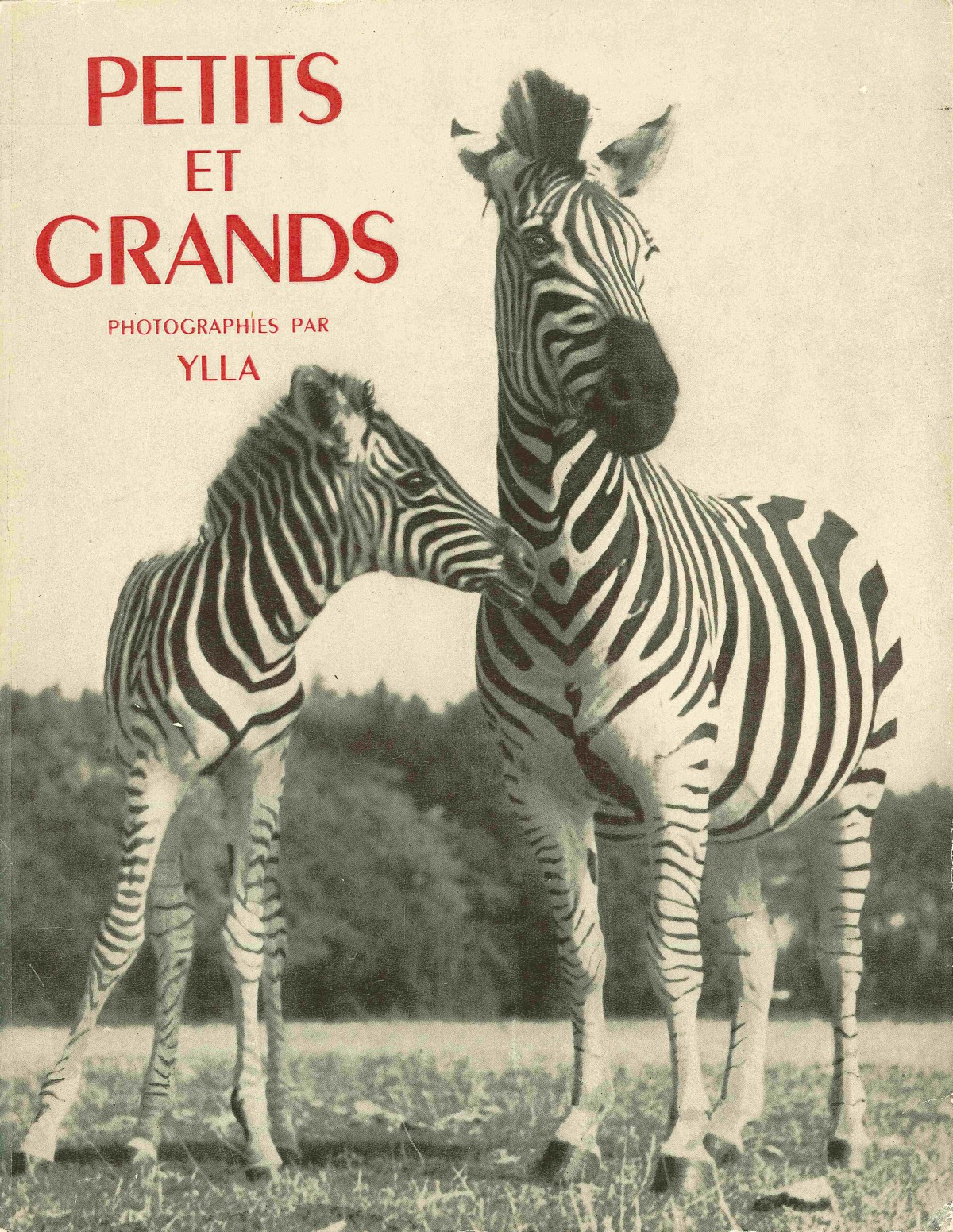

Ylla began taking photographs in 1932. From the beginning, however, her models were not people, but animals, which she photographed according to her contemporaries in a way never seen before, namely not as props, but as living individuals. Her choice reflected the deep conviction of a kinship: “When I find myself among cows or giraffes, for example, we are immediately ‘entre nous,’” reads a note from the 1930s. The first article about her photos appeared in 1933. That same year she exhibited for the first time and opened her first photo studio, the only portrait studio for animal photography in Paris at the time, with money that Landau lent her. With energy and inventiveness, she found ways to make her target clientele aware of her work, for instance, by writing to veterinarians and asking them to recommend her services to the owners of their four-legged patients. In 1935, Ylla published her first two photo books, Chiens (Dogs) and Chats (Cats), which were followed by numerous other books, and she had postcards of her photos printed. Her animal pictures also frequently appeared in the illustrated press.

Ylla began taking photographs in 1932. From the beginning, however, her models were not people, but animals, which she photographed according to her contemporaries in a way never seen before, namely not as props, but as living individuals. Her choice reflected the deep conviction of a kinship: “When I find myself among cows or giraffes, for example, we are immediately ‘entre nous,’” reads a note from the 1930s. The first article about her photos appeared in 1933. That same year she exhibited for the first time and opened her first photo studio, the only portrait studio for animal photography in Paris at the time, with money that Landau lent her. With energy and inventiveness, she found ways to make her target clientele aware of her work, for instance, by writing to veterinarians and asking them to recommend her services to the owners of their four-legged patients. In 1935, Ylla published her first two photo books, Chiens (Dogs) and Chats (Cats), which were followed by numerous other books, and she had postcards of her photos printed. Her animal pictures also frequently appeared in the illustrated press.

Ylla, Petits et grands (Big and Little), 1937

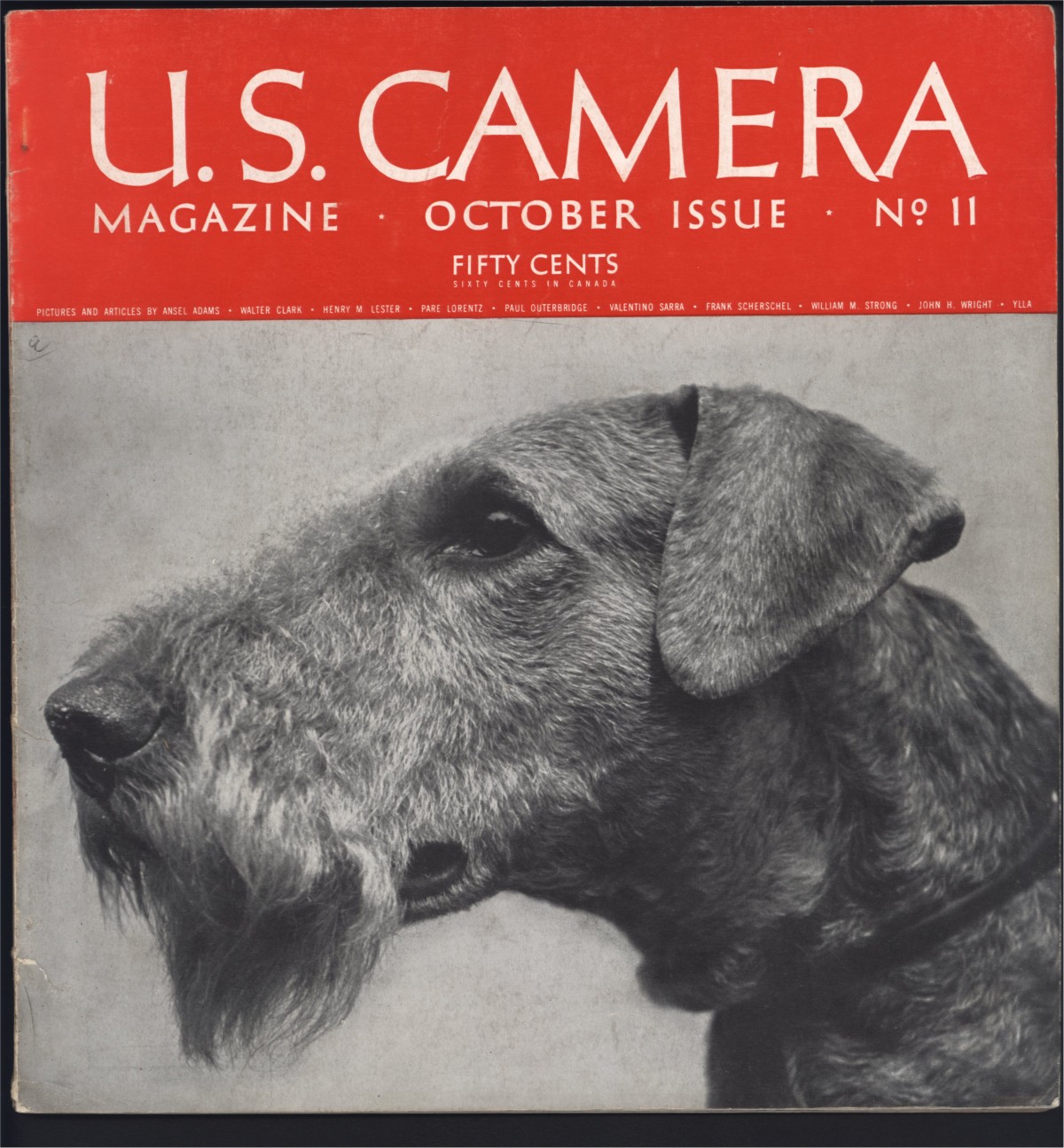

Photo of Ylla on the cover of US Camera, no. 11, October 1940

But Ylla also repeatedly became a model, often for Ergy Landau, who specialized in artistic nude photography. In other photos, Ylla is shown privately, for example, with friends or in a bathing suit on the beach. In these photos, she is almost always seen laughing. The second half of the 1930s must have been a happy time for Ylla. She had made many friends and was a shooting star in what was then the world capital of photography and not only there: she had also attracted attention at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York. Her success and fame continued to rise until the Second World War began in 1939 and demand for animal photos collapsed. Suddenly her status as a foreigner also played a role. She considered all possible scenarios such as a fictitious marriage with a Frenchman or emigrating to the USA. Just a few days before the Wehrmacht invaded in June 1940, she fled Paris and made her way to Marseille on adventurous paths, from where she was able to travel to New York with a visa supported by MoMA and a passage paid for by Varian Fry1. Her friend Ergy Landau, who, like Ylla, was in danger as a Jew, remained in Paris and survived the period of German occupation.

Arriving completely penniless in New York on June 6, 1941 following a year-long odyssey, Ylla was able to continue her work immediately with the help of friends and thanks to her fame in professional circles. She soon garnered success again in the USA, although not exclusively because of her photos: Ylla herself, the young, attractive, and fearless animal photographer, generated publicity. As Ylla expert and estate administrator Pryor Dodge describes in his monograph published in 2024, the photographer repeatedly found herself in dangerous situations from which she mostly emerged unscathed. However, one time a panda she wanted to photograph bit her thigh. The positive media response to this incident increased her fame in the USA and boosted her career at a time when she really needed it. As of the end of 1941, she was able to rent a penthouse with a terrace as a studio and apartment and to travel, initially within the USA. In 1952, she visited Africa for the first time, and in 1954/55 India.

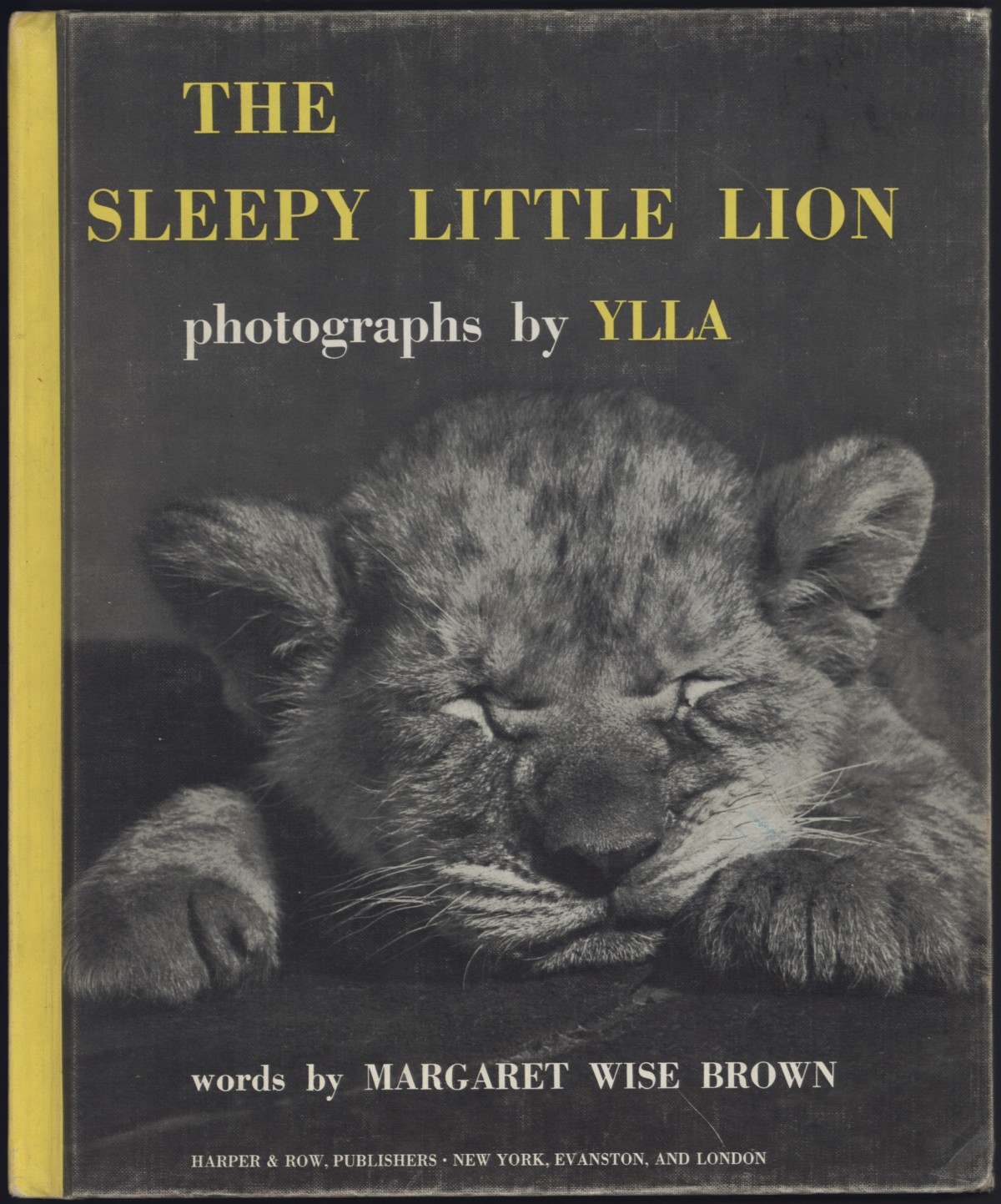

Ylla, The Sleepy Little Lion, 1947

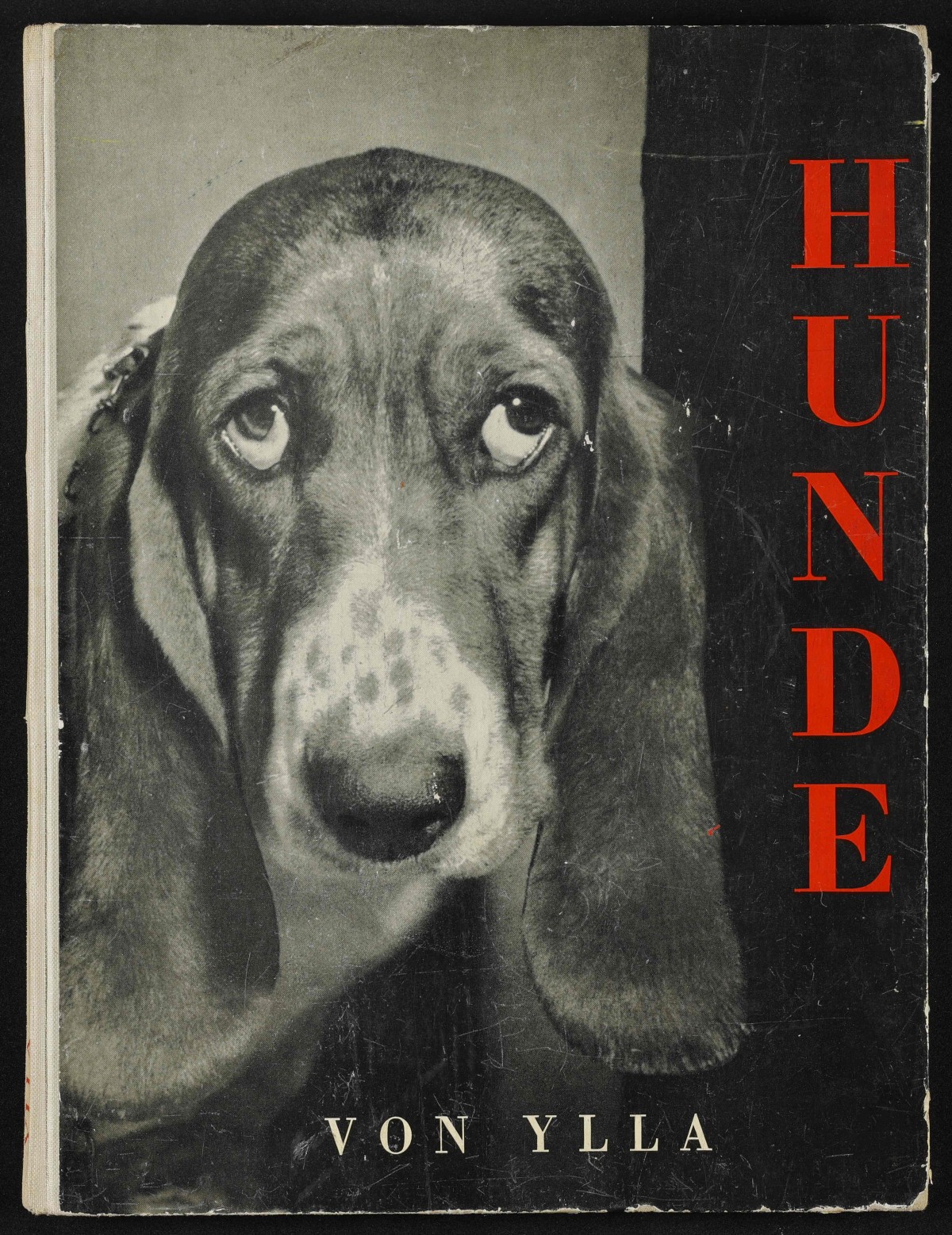

Ylla, Hunde (Dogs), 1956

In the end, however, Ylla’s fearlessness led to her far too early death. Inspired by the Technicolor film The River (1951) by the French director Jean Renoir, which was shot on the banks of the Ganges, she accepted an invitation from the Maharajah of Mysore to India at the end of 1954. On March 29, 1955, she insisted on photographing a bullock cart race in Bharatpur from the hood of a moving jeep, disregarding her own safety. When the jeep drove over a bump at high speed, she was thrown off and suffered a serious head injury, from which she died the following day.

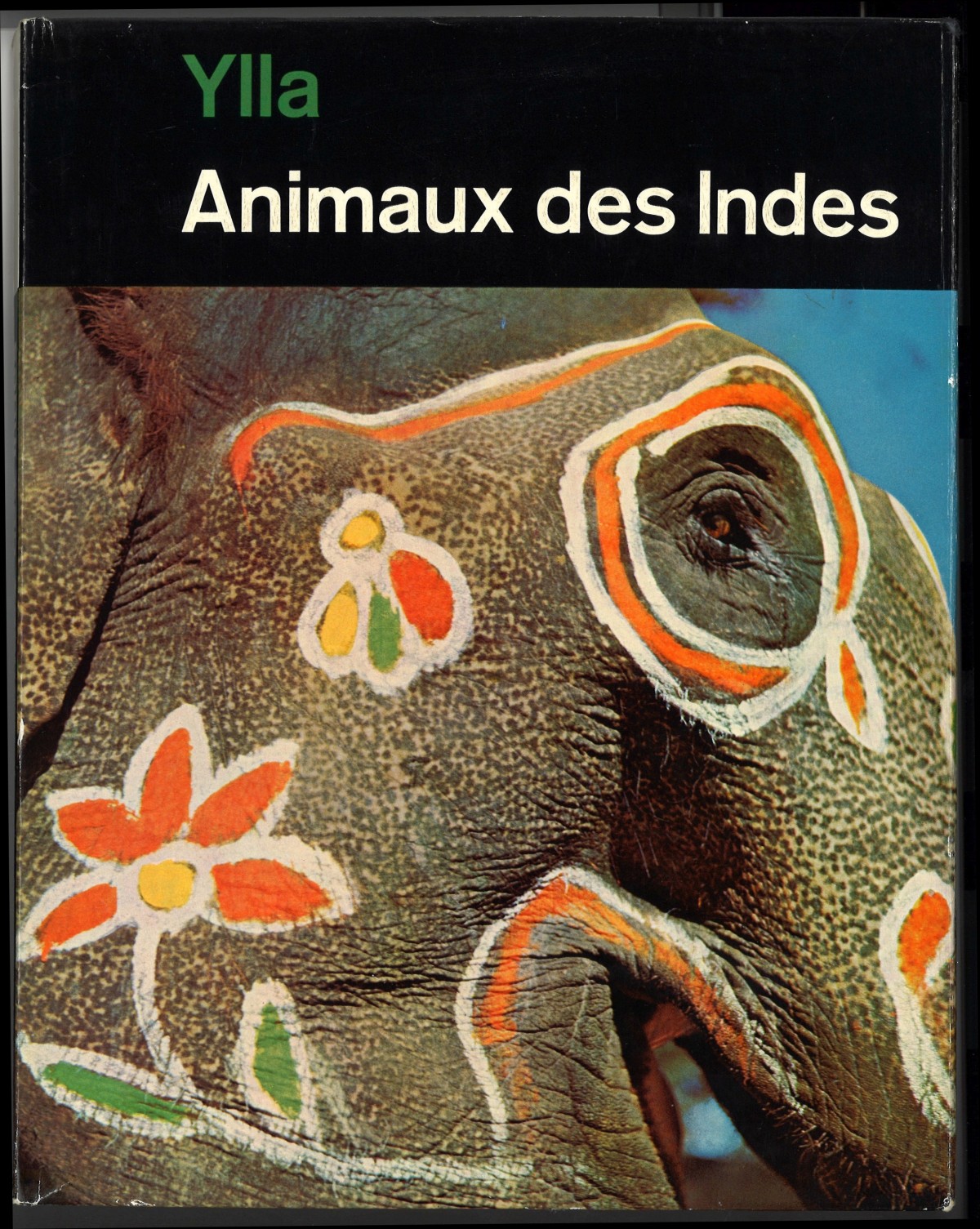

Ylla, Animaux des Indes (Animals in India), 1958

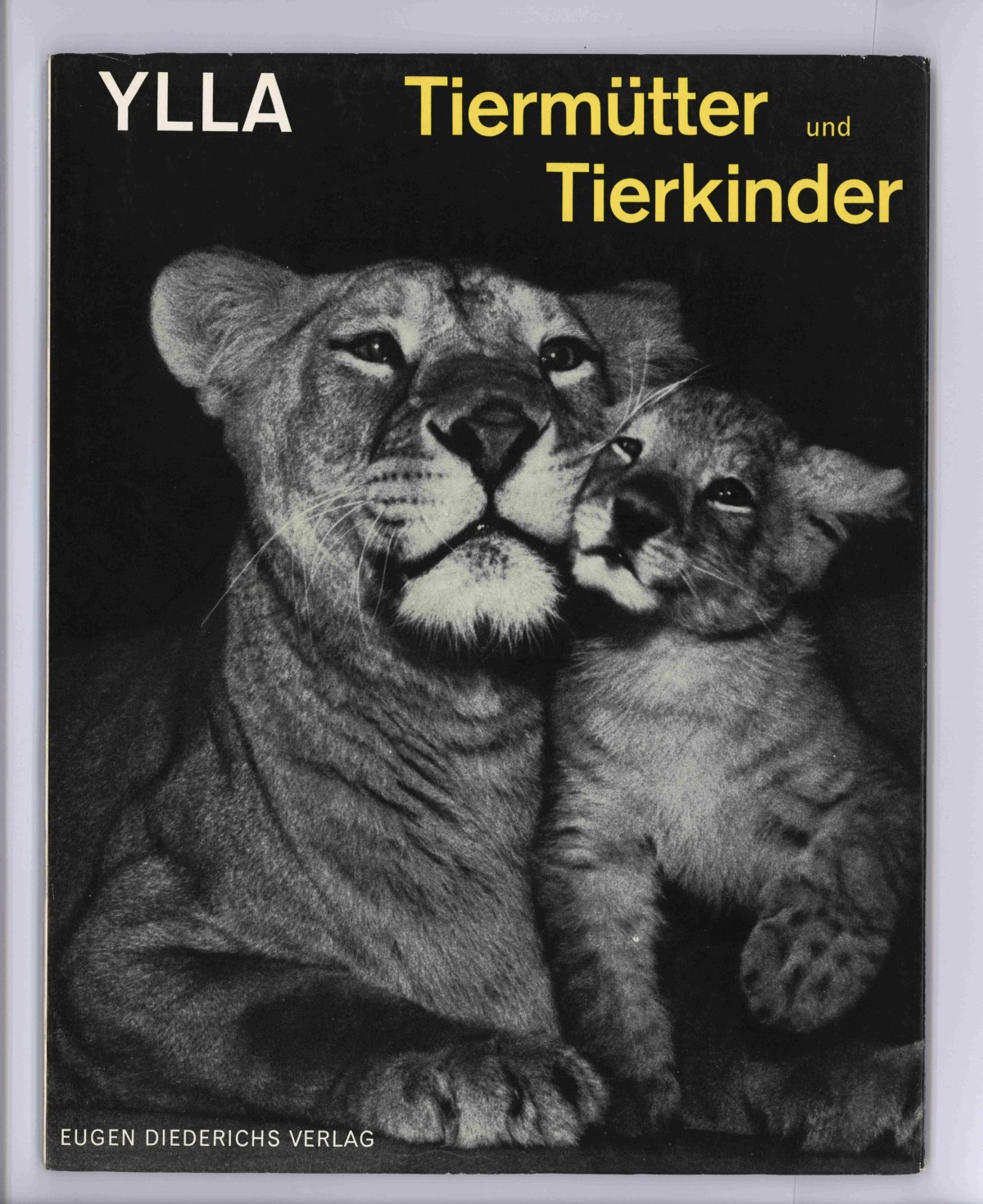

Ylla, Tiermütter und Tierkinder (Animal Babies), 1959

As an adventuresome photographer of wild animals, Ylla entered popular culture not least through the reporting on her death and the numerous publications of her photos from India. Several of her photo books were published posthumously. In 1957, two comics about her eventful life were published, one in France and one in Belgium. Director Howard Hawks was inspired by Ylla to create a film character for his 1962 Africa film Hatari! (Swahili for “danger”). Ylla took risks because this not only enabled her to capture more unusual images, but also to attract the attention of the press herself: Here was a woman who did what her male colleagues did not dare to do a fatal unique selling point. Ergy Landau’s photo of a laughing Ylla at the Paris Zoo shows them performing her life-threatening work.