“... that I owe it to them to defend them against the abuse of their history and their family’s history.”

Memories of Robert Rotifer, in conversation with Barbara Staudinger

Robert Rotifer, born in Vienna in 1969, is a musician, a print and radio journalist, and has lived in England since 1997. His grandmother was the well-known Viennese resistance fighter and communist Irma Schwager, who was born as Irma Wieselberg in 1920 into a Viennese Jewish family and died there in 2015. Politicized at an early age by the socialist-Zionist youth movement Hashomer Hatzair, Irma Schwager had to flee Austria at the age of 18 because of her Jewish origins. She found exile in Belgium, fled to France after the invasion of the German Wehrmacht in May 1940, and was detained at Gurs and other internment camps. where she became a member of the Communist Party of Austria (KPÖ) group. Having managed to escape from the camps, she joined the resistance, was active under a false identity and thus able to survive. After the war, she returned to Vienna with her husband, the Spanish Civil War fighter Zalel Schwager (1908–1984), and her daughter, who was born during the war, and was active in the KPÖ and as an outspoken witness to contemporary history throughout her life.

(Barbara Staudinger – BS) When did you first hear about your grandmother’s story and from whom?

(Robert Rotifer – RR) The family, resistance, and camp stories have been present for as long as I can remember, even since I became self-aware. Who am I and where do I come from? Why does everyone call you Nicky, mummy, even though your name is Monika? “Because as a small child, my name was actually Monique in French, but I couldn’t pronounce my name. Apparently I always called myself ‘Nique.’” This naturally raised the question: Why French? “Because I was born in France, in a city called Lille. But under a false name.” Why was that? “Because Grandma and Grandpa lived in hiding because the Nazis were after them

” And so they had to explain everything to me, there was no way around it. Including the question of why we had so few relatives compared to other children. Why once, when I was still small, these relatives from this “Israel” came to visit. Who was that boy my age who I played so well with, even though he could hardly speak German? Who looked so much like me that when I saw him in photographs I confused him with myself? “That is the grandson of Irma’s brother Oskar,” they said, “he died because it was much too hot for him in Israel. Irma-Oma had two other brothers, but they have been dead for a long time because they were killed by the Nazis

” Whatever was discussed on my mother’s side of the family, it all came back to this topic at some point. And the question of how Irma and Zalel had survived also arose by itself. My parents were basically honest with my sister and me; they didn’t make up any fairy tales. They probably spared us the worst details, but my childish imagination filled in the gaps. From a young age I always had the same nightmares. That I would have to flee and hide. I was terrified of the army and all kinds of soldiers. I imagined military service to be like one of those “camps” that I had been told about. My grandfather Zalel was still alive when I was a child. We had a very close relationship until he died when I was 14. He was a very wise, dignified man, a pipe smoker, short with thick, wavy black hair, always in a white shirt and trousers that reached almost to his chest. Zalel was 12 years older than my grandmother and had experienced imprisonment and deportation in the First Republic and the Austrofascist dictatorship but above all the Spanish Civil War by the time he met Irma at the French camp in Gurs. I only found out much later from other sources what life was like there, how lucky they were to survive the inhumane conditions there. They never told us any more details about that either. But Zalel was still one of my most important sources of information because he always took me and my questions seriously, even though I was still a small child. Irma was still working at the time; she was the successor to her friend, the architect and resistance fighter Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky, president of the Federation of Democratic Women, a pro forma independent women’s movement that was de facto part of the KPÖ, and as such was constantly on the move, always at conferences or meetings. My long conversations with her at the kitchen table only happened decades later.

30. October 2024

Asked!

The Third Generation in dialogue: Robert Rotifer

by Barbara Staudinger & Robert Rotifer

Accompanying and complementing our current exhibition The Third Generation. The Holocaust in Family Memory, we conducted interviews with relatives of the Third (and sometimes also the Fourth) Generation and asked them about their quite personal dealing with the story of their grandparents, as well as about the perception of their generation. You can read these very diverse results in our museum blog or watch them as videos.

© private

Zalel, Irma, Ernst und Monika, ca. 1950

© private

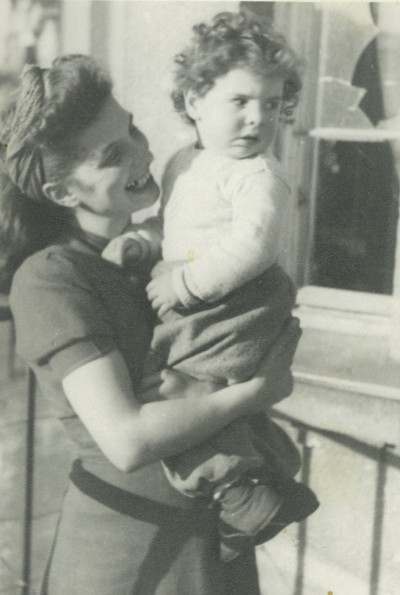

With my newly born mother, Tourcoing/Lille, 1944

(BS) I tried to briefly outline the life of Irma Schwager. Are there any aspects that you would like to add or that you consider particularly important?

(RR) So much. There is an unwritten book, so to speak, that I cannot possibly go into here. But I would like to highlight two things: My grandmother did not deny her Jewish origins; in many ways she was a classic assimilated Viennese: salted fish at Christmas, lots of Yiddish words in the family vocabulary, but decidedly non-religious. She and Zalel, who grew up Orthodox as the son of a Brigittenau mashgiach, consciously turned away from religion out of Marxist conviction. But of course that did not change the fact that they were persecuted simply because of their origins. My grandfather fled the pogroms in Galicia with his family as a small child. Irma was born in Vienna, but her parents came from the Lviv area. Nevertheless, it was always very important to Irma that her story was part of the liberation of Austria. Like so many who had switched from the Zionist movement to social democracy or communism, she was concerned with building a better society for everyone in the place where she lived. She would not allow this aspiration and this place to be taken away from her. I do not believe that she saw herself as part of a diaspora, but as part of this city, part of this country. Because that was the great goal that kept Irma, Zalel, and their Austrian friends together in French exile, across political and religious boundaries: to liberate Austria. Even if they then returned to a country where none of their family existed anymore. Their few surviving siblings had not returned, only Irma and Zalel were there. But they had comrades around them as a surrogate family who had also made the same decision. The Wintersteins, Hermann “Onkel” Wenkart, Ephraim Feuerlicht known by his alias Franz Marek, who was a friend of my grandfather's, all these names from the Jewish-communist universe that I was familiar with from childhood.

But there is another important thing that I have to say on Irma’s behalf, because she can no longer do it herself: the most important issuethat she kept coming back to was “peace.” She was a communist, but certainly not a theoretician or an ideologue. One can rightly accuse her of remaining loyal to the party line when that took a lot of self-deception for a humanitarian like her – my grandfather, on the other hand, withdrew from all party activities as a silent form of protest – but the core of Irma’s message, her highest ideal, was peace, unshakably, so. The avoidance of bloodshed as a civilising commandment. I think one has to respect that as her way of dealing with the horrors of war she had experienced herself. That was not naivety, but a principle acquired under terrible circumstances, which is a big difference. In that respect, I am often glad that Irma did not have to live through our present times.

(BS) Irma Schwager was active as a contemporary witness for a very long time; her political life and her anti-fascist struggle are well known to many. As a grandson, were you able to approach her life differently, perhaps through personal stories?

(RR) That is a very good question, because there was an important aspect of her being a witness to contemporary history that many other children of the “third generation” will probably recognize: Yes, my grandparents argued loudly and passionately, whether among themselves, with my social democrat parents, or with my uncle Ernst. No difference of opinion was taboo. But although my grandparents had fought on the good side and for the good cause, so to speak, they did not like to talk about their personal experiences in this struggle, and certainly not publicly. I know that Ernst, for example, was very annoyed when Irma was asked directly on a television discussion program about her experiences of the 1938 pogroms, and only answered in the usual well-worn phraseology. Her own, elderly father had been dragged out of his wheelchair and onto the street by the fanatical, Aryan neighbors to wash the pavement. One of Irma’s brothers then took the brush, rolled up his sleeves, said “No problem, I’ll do it,” and proceeded to scrub in his father’s place. Irma herself told the story that she simply knocked over the bucket of water that the mob had handed her in front of the house and rode off on her bicycle One found out about these things from time to time in conversation, but they never appeared in Irma’s many speeches. I understand today that much of it was self-protection. Irma and her husband kept the past at a distance. It was not only the perpetrators who repressed the past, but also the survivors. Not only because of their oft-quoted feelings of survivor's guilt, but also because it simply hurt too much to talk about those who were murdered. I am convinced that they were haunted by these ghosts anyway, so why parade them around as well?. I know that my grandfather would reprimand my mother and uncle when they asked Irma probing questions about her family and she would start to cry: “Can’t you see what you’re doing?” It was only in her later years that the distance in time was long enough to talk about personal things. But even these stories tended to be about relatively harmless things. For instance, how Zalel had suffered in France because Irma was always late for every rendezvous. According to protocol, he should have left without waiting for her because if somebody was late, it had to be assumed that their cover had been blown. It was only later that I understood how many women like Irma, who did the “girl’s work” of spying on and demoralizing German soldiers in the Resistance, were actually tortured and killed. It was one of the most dangerous activities in the Resistance. Whenever we were in Vienna in Irma’s final years, my wife and I stayed at her flat and talked over long breakfasts about things like smuggling leaflets in empty toothpaste tubes. And how Irma often narrowly avoided being discovered.

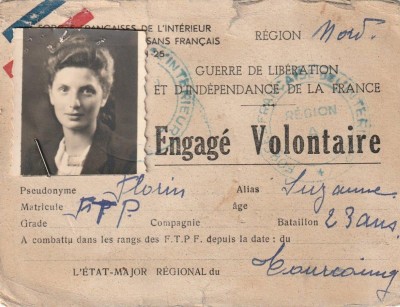

© private

Identity card as a member of the Franc Tireur Partisans (FTP), under the ‘pseudonym’ Suzanne Florin, probably after the liberation in September 1944, although she would have been 24 by then

© private

In Brussels, 1938

(BS) How did the story of your grandparents and the Holocaust influence your life?

(RR) The impact of the Holocaust on my origins and the non-existence of large parts of my family gave me a lifelong feeling of distrust of Austrian society, which unfortunately has been confirmed time and again: When I played for a football club as a child in the late 1970s and the coach said, “He’s hit a Jew!” when someone hit the ball with his toes instead of his instep. “That’s just what they say,” my teammates explained to me. Or when the fans of city rivals Rapid openly chanted “Jewish pigs” in unison at the FK Austria Wien supporters in the stadium. When, during my national service in the 1990s, which I served as a paramedic, a full-time colleague confided to me in a hushed, conspiratorial tone after delivering a patient to the psychiatric hospital Baumgartner Höhe: “We would have gassed them all.” Or many years later, at an embassy reception in London on Austrian National Day, when, after asking a few questions about my origins, a nice woman assured me that “everyone had a hard time during the war,” even the “normal Austrians,” though “you never hear anything about that.” In contrast to my grandmother, the staunch Austrian who even wore the dirndl, which was forbidden to Jewish women before the war, when she went hiking, these experiences always made me deeply sceptical of any kind of patriotism. I simply cannot go along with it, even if it is “well-intentioned.” I am Austrian, but I prefer to keep a safe distance. I was also surprised that today, at this point in my life, the aspect of my origins derived from the Holocaust experience would haunt me in such an emotional way. I was not prepared for this. It is the shameless exploitation of the Holocaust for political purposes that I find profoundly hurtful. Particularly when the descendants of the perpetrators construct a moral calling from their legacy. I am deliberately phrasing this so openly because, in my experience, it is better when people feel that this might be about them than when you put something to them directly. That way they get the opportunity to think for themselves about what they are actually saying and doing. I find the misuse of the memory of the Holocaust and the way people paint the threat of a possible next one as a justification for racist hatred or collective punishment of a population to be almost physically unbearable. But this is not about me at all. I know my departed grandparents well enough to know what they would have thought of it. And I feel that I owe it to them to defend them against the misuse of their history and their family’s history. I am aware that the same feeling will lead others to a completely different conclusion. Others still will be content to use the right phrase here and there, otherwise be diplomatic and not offend anyone, but I don’t have that luxury. And by protecting the memory of the Holocaust from abuse, I don’t mean rejecting every Holocaust comparison. Because one always has to be able to compare, otherwise one is taking away one’s own means to recognising the recurrence of thoughts and actions that led to the Holocaust.

(BS) You have musically dealt with your grandmother’s life. Did that change your connection to her?

(RR) Irma always respected my musical inclinations but wasn’t particularly interested in music herself. In 2000 I wrote a song about Zalel called “Blue to Brown,” the title referring to the change from blue to brown shirts, as he must have experienced it himself, and how I would describe the modern version of it I am now experiencing myself. We remember that 2000 was the year the Freedom Party of Austria (FPÖ) first took part in government. “I’m glad you didn’t see this day” was the key line from the song, which I keep thinking about today in relation to Irma. I wrote two songs about Irma herself, but only after her death. The first of these was when I was asked to play at her funeral serviceat the crematorium. It occurred to me that there was no song that really applied to her, so I had to write one. I didn’t have much time for it, but it came surprisingly easily. I allowed myself the level of abstraction of writing in my everyday language, English, even though the song is set in Vienna. It is called “Irma la Douce,” and the lyrics are a kind of tour of the apartment on Schüttelstrasse that she, Zalel, and my one-year-old mother moved into in the summer of 1945. The municipal housing office had allocated it to them. At that time, my grandfather had been entrusted by the Soviet occupying forces with recruiting a new police force made up of men who, if possible, had no Nazi past, and there were not many of them in Vienna. Befitting these circumstances, he and his family were given this empty apartment on the Danube Canal, which had just previously been home to a Nazi officer’s family. The Böcklinstrasse, Schüttelstrasse quarter was then known as the “brown roof” of Vienna because Nazi officials had stolen these apartments near the Prater from middle-class Jewish families. This hardcore Nazi group had held out there until the end and had been shelled by the Red Army across the Danube Canal from the Third District. As a result, the outer wall of the apartment had a grenade hole that had to be bricked up to make it habitable. Seventy years later, one could still see a bullet hole from a ricochet in one of the living room doors. The description of this leads me to the final lines of the chorus: “Irma la Douce, tell me the truth. What made you come back home? ‘We came because we won.’” This was a direct quote from her answer to the question I had asked her on her 90th birthday: “Irma, I am grateful because otherwise I would not be here today, but I have never understood this: Why did you come back to Vienna?” Her answer came immediately, without any hesitation: “Well, because we won.” That actually explains her attitude better and more concisely than anything I tried to put into my own words earlier.

My second song about Irma was “Not Your Door,” written a few days after the funeral. I was about to set off back to England and wanted to stop by the apartment one more time, browse through Irma’s letters one more time, see Zalel’s desk that had stood unchanged for decades, run my fingers along the furniture. And it was only when I was there that I realized that I didn’t have any keys with me. That Irma couldn’t open the door for me because she wasn’t there anymore. That the balcony up there was no longer hers, and the front door wasn’t hers either. To come back to the question: It didn’t actually end my connection to her, but changed it. Since her death, she no longer lives on Schüttelstrasse, but in my head. She is always with me now.

© private

With my mother in the flat they had just moved into on Schüttelstraße, 1945

© private

With my one-year-old mother, Brussels 1945

(BS) Is there a memory or an object that you would particularly associate with Irma Schwager? Why did you choose this memory, this object?

Irma had a particularly energetic way of washing dishes, which often resulted in a lot of things going to pieces, including various parts of her crockery, Acapulco by Villeroy & Boch. I always associated this set of dishes with her because it matched both her solidarity with Latin American resistance movements and her penchant for peace doves of all kinds. But also because she served her equally energetically prepared, reliably delicious apple strudel on it. After Irma’s death, when we were allowed to keep something from her belongings, my wife and I chose the few surviving cups, plates, and egg cups. We use them almost every morning.

© private