If we hadn’t been hearing or reading about Ukraine every day since February 24th of this year, a different text would have been published here. Anything other than “Ukraine” would have been the search term for a journey into the museum’s collection, into its heart, which would have led through Vienna or some other place. With some knowledge of history, the fact that “Ukraine” appears seventy-four times in the inventory of the Jewish Museum Vienna may not come as a surprise. After all, Jewish settlements had existed in what is now Ukraine as early as the Hellenistic period. The Krymchaks and the Karaites, who opposed rabbinic Judaism, lived on the Crimean Peninsula. A Moses of Kyiv is cited by Meir von Rothenburg, a prominent German rabbi of the Middle Ages.

Since 1340, the western part of Ukraine had belonged to the Kingdom of Poland and the freedom of trade and religion were widely granted. Under King Zygmunt I, the Polish Kingdom experienced its height of power as of 1506 and the Jewish communities flourished. After the First Partition of Poland in 1772, Russia received the northern part with the regions of Volhynia and Podolia, while Austria gained the southern part with Galicia. In the mid-nineteenth century, Jews made up the largest population group in many cities. Due to pogroms in the 1880s and the following years, many of them emigrated to central or western Europe and the USA.

Instead of a more detailed presentation of the cultural-historical connections between cities such as Lviv, Odessa or Brody and Vienna and the Jewish Museum – the first one and the present-day one – this article does not to list and describe the famous names and facts, but to draw attention for a moment to how close the almost one thousand kilometers that lie between “Our City!” and the Ukrainian border are.

22. April 2022

Vienna and the World

About near and far

by Hannah Landsmann

Jenny Wagschal is the mother of Paul Peter Porges, whose family came from Chernivtsi/Czernowitz and sold Singer sewing machines. We see her here as a young girl who later lived with her husband Gustav and their sons Kurt and Paul Peter in Vienna’s fifteenth district. Her two sons were able to be rescued through a Kindertransport to France. Paul Peter became a cartoonist and used his nickname PPP, as he had already been called in Vienna, as his artist’s name. Closely associated with the Jewish Museum Vienna already during their lifetime, he and his wife Lucie continue to be, since an extensive stock of archival material was transferred to the museum’s collection.

© Jüdisches Museum Wien

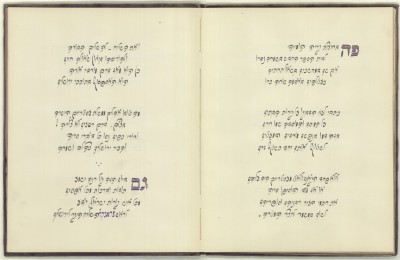

The sons of the physician, archivist and 1848 revolutionary Ludwig August Frankl gave the old Jewish Museum in Vienna a Hebrew poem on October 22, 1895, the year in which the institution was founded. Handwritten and bound, with a Hebrew dedication inscription, the poem was a gift for the seventieth birthday of Dr. Ludwig August Frankl, Ritter von Hochwart. The author of the celebratory poem “Yerushalayim Habnuya” is Isac Jonas Grünes from Lviv. Lemberg, as Lviv is called in German, was one of the most important centers of Jewish Eastern Europe. With great euphoria, Ludwig August Frankl campaigned for the German poet Friedrich Schiller to be honored with a statue in Vienna. Until then, the erection of a statue in a public square in Vienna had solely been reserved for rulers and generals. The unveiling took place on November 10, 1876 in the square in front of the Academy of Fine Arts. The Goethe Monument, erected in 1900, stands opposite.

© Jüdisches Museum Wien

© Jüdisches Museum Wien

According to the inventory catalog of the old Jewish Museum, the small Bible, measuring just 3 x 2 centimeters, was acquired in 1934 by curator Dr. Jakob Bronner from the estate of the Rebbe of Jezierna. Located around one hundred kilometers southeast of Lviv in modern-day Ukraine, Jezierna (Ozerna in Ukrainian) was a typical East Galician shtetl with a Jewish majority in the population, most of whom adhered to Hasidism. From the second half of the nineteenth century onward, many Galician Jews immigrated to Vienna, including several Hasidic rabbis from famous dynasties who opened private houses of prayer in Vienna. It is quite possible that the Rebbe of Jezierna gave the little book to the museum during a visit to Vienna. Originally containing 605 pages, the miniature Bible now only partially exists up to the First Book of Kings. A metal cover and an integrated magnifying glass, mentioned in the inventory book, are also missing.

On January 2, 1904, this object was acquired by Dr. Samuel Weissenberg as a loan to the old Jewish Museum. It is a so-called Haman clapper which, like the more well-known Purim graggers, is used to drown out the name of Haman, who wanted to kill the Persian Jews, when the Esther scroll is read on Purim. The rattle was made in the town of Novogeorgievsk, which now lies at the bottom of the Kremenchuk Reservoir created in the course of the damming of the Dnepr River starting in 1962. Samuel Weissenberg, a physician and ethnologist, provided the first Jewish Museum with numerous items on loan, which testify to the institution’s interest in folklore and the focus of its collection on Eastern Europe.

© Jüdisches Museum Wien

© Jüdisches Museum Wien

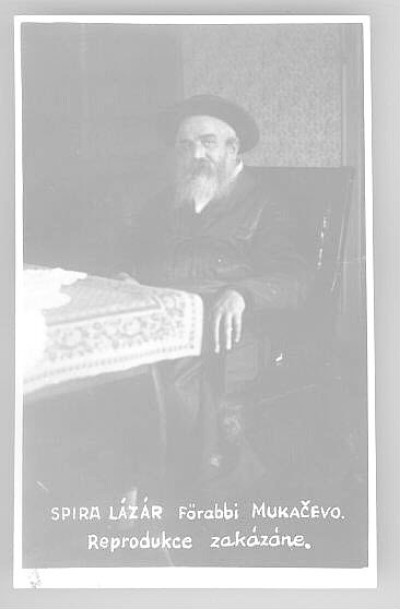

The man pictured is Chaim Elazar Spira, the Chief Rabbi of Mukachevo (German: Munkatsch). Spira was born in Strzyżów in Galicia in 1871 and died in Mukachevo in 1937. Spira is the Latin name of the German city of Speyer and Mukachevo is called Mukačevo in Slovak and Munkács in Hungarian. Located in western Ukraine’s Transcarpathian Oblast, the city has around 85,000 residents today. Fourteen kilometers southwest of Mukachevo lies the village of Nagylucska (Velyky Luchky), where Heinrich Niszan Chaim Edlisz was born on June 3, 1893. He lived in Vienna as of 1913 and married Gisella Kallus, who came from a village not far from Mukachevo, on May 8, 1921. One of the young couple’s neighbors at Liechtensteinstrasse 130 in Vienna’s ninth district was Dr. Jakob Bronner, the curator of the old Jewish Museum already mentioned here. Gisella and her three children, Lotte, Stefan and Herbert, were finally able to leave Vienna in 1941. Stefan carved out a great career in his new homeland and became one of the most important collectors of contemporary art. The current exhibition (Un)Pleasant Journey. The Life of Stefan Edlis after HIM is dedicated to his moving and eventful life story.

In 2004, a Japanese visitor to the Jewish Museum in Vienna gave the archive eleven color photographs he had previously taken on his trip to Brody. Not much can be seen in the relatively small pictures – except that what used to be there no longer exists.

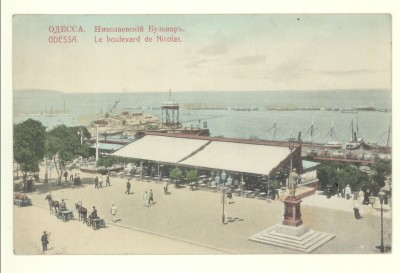

Likewise originating from Japan is the famous hare with the amber eyes that was on display in the Ephrussi family exhibition, along with numerous other netsukes and objects from the family archives. The Ephrussis had become wealthy in Odessa with the wheat trade. The Ephrussis traveled and later had to flee from Odessa to Vienna and Paris, to Spain, South America, the USA, Great Britain and as far as Japan. Edmund de Waal’s best-selling book introduced the Ephrussis to a broader public.

Likewise originating from Japan is the famous hare with the amber eyes that was on display in the Ephrussi family exhibition, along with numerous other netsukes and objects from the family archives. The Ephrussis had become wealthy in Odessa with the wheat trade. The Ephrussis traveled and later had to flee from Odessa to Vienna and Paris, to Spain, South America, the USA, Great Britain and as far as Japan. Edmund de Waal’s best-selling book introduced the Ephrussis to a broader public.

© Jüdisches Museum Wien

© Jüdisches Museum Wien

© Jüdisches Museum Wien

This postcard, featuring a very light blue sky, was specially made for the exhibition The Ephrussis. Travel in Time. The core of the exhibition was the Ephrussis family archive, which the de Waal family donated to the Jewish Museum Vienna in 2018, as well as 157 netsukes, which the family made available to us on long-term loan. The first room in the exhibition enabled visitors to travel to Odessa, but did we all immediately think of the Ukrainian flag back then? Probably not. Although the yellow signifies the color of the wheat.